Incorporating Weather Days into Your Project’s CPM Schedule

An often-debated question is “How should a project schedule incorporate the workdays that might be lost to adverse weather?”

While there is not one perfect solution for all projects, there are at least three approaches to incorporating weather into your CPM schedule. These approaches are:

- Incorporating non-workdays into the schedule’s work calendars to represent the workdays that might be lost to adverse weather.

- Increasing the durations of weather-sensitive work activities to represent the workdays that might be lost to adverse weather.

- Adding an “adverse weather” activity at the end of project with a duration that equals the number of workdays that might be lost to adverse weather.

(Of course, there is always a fourth option, which is to assume that every day lost to weather will be made up by working on Saturdays or by working overtime. If this is the assumption upon which both your costs and your schedule are based, and both your contract and your other team members are on board, then you may not have to bake any weather into your schedule at all.)

Each of these three options (except the one in which you do nothing to the schedule) will be discussed in more detail below.

1. Incorporating Adverse Weather Workdays in Work Calendars

In CPM scheduling software packages, users have to create or modify work calendars that identify when the contractor plans to work. For example, the most common work calendar is an 8-hour-per-day, 5-day workweek calendar that includes holidays and weekends as non-workdays. Each schedule activity is assigned to the work calendar that best represents when that particular work activity will be performed.

One way to account for adverse weather is to identify days that would otherwise have been workdays as non-work days in the work calendars.

The advantage of this approach is that the contractor can show that it separately accounted for anticipated adverse weather in its project schedule by simply referencing the calendars that have adverse weather workdays built into them. It also provides a somewhat realistic depiction of when the project might incur adverse weather conditions and, thus, may more accurately forecast the dates that work will actually be performed on longer projects.

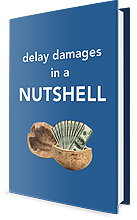

For example, let’s say the contract states that the contractor should plan to lose 4 workdays to adverse weather in the month of June. The default 5-day workweek calendar for June includes no holidays and, therefore, every weekday is an available workday (see Figure 1, below).

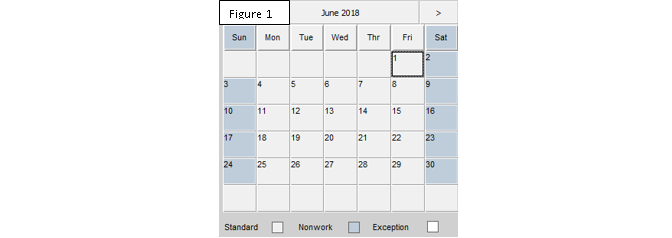

In this scenario, to accommodate the contract’s requirement to assume 4 workdays lost to adverse weather in June, this calendar could be modified to block out 4 workdays as non-workdays. In Figure 2, below, 4 of the Fridays in June have been identified as non-workdays.

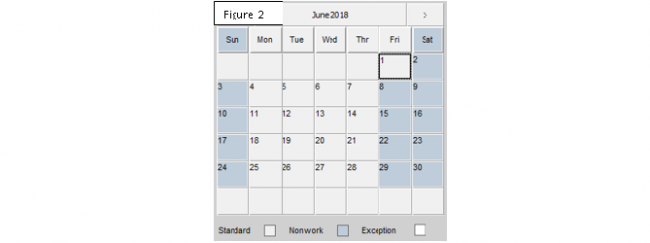

Another option is to create project or activity-specific work calendars for operations that are subject to additional working restrictions. An example of a project-specific calendar is a weather-sensitive or winter work calendar for activities that are subject to seasonal or winter work limitations. In these work calendars, all of the workdays in the winter months are identified as non-workdays in the work calendar.

For example, let’s say that there is hot mix asphalt (HMA) paving work required on a highway project, and the contract requires that “no base paving (HMA) placement will occur between November 15 and April 1 without the written permission of the Engineer.” In this scenario, a work calendar could be created that specifically includes these work restrictions by marking all workdays during that time period as “non-work” (see Figure 3, below).

The primary criticism of blocking out non-workdays in advance for adverse weather is that no one can predict when it will rain or snow in the future, and when work won’t be able to occur. For example, some work that usually cannot occur during the winter can and is performed, particularly if the winter is unusually mild. However, by including the anticipated non-workdays due to adverse weather in work calendars, it is possible to ensure that the contractor’s plan, as depicted in the project schedule, provides a realistic forecast of when future work is planned to occur by accounting for workdays that might be lost to adverse weather in the project schedule.

Note that the success of this approach depends on the how carefully and honestly the contractor puts the schedule together. For example, many times the owner does not identify the number of days that the contractor should plan to lose to adverse weather. Even if the contract does provide a number, the contractor may not be obligated by contract to incorporate these days into its work calendar. Lastly, contractors may address weather delays differently than the schedule assumes. For example, if the contractor plans to work Saturdays or overtime to overcome weather-related delays, then some owners might take the position that a certain number of Saturdays should be added workdays – in addition to blocking out workdays for adverse weather.

2. Increase Durations of Weather-Sensitive Work Activities

A second way of accounting for or incorporating anticipated workdays lost to adverse weather into the project schedule is to increase the durations of the weather-sensitive work activities. This approach is as simple as it sounds. By simply increasing durations for activities that may be subject to adverse weather, those activities will then take into account the anticipated delay from that adverse weather.

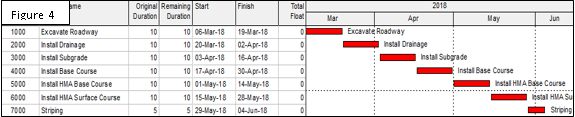

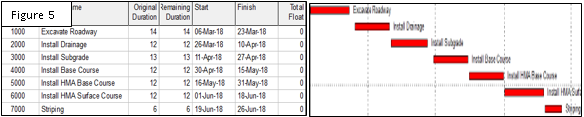

For example, for a basic roadway project, a simple schedule is identified in Figure 4, below. This schedule does not take into account workdays that might be lost to adverse weather.

Assume that the contract for this project states that the contractor should anticipate losing 6 lost workdays in March, 5 lost workdays in April, 4 lost workdays in May, and 4 lost workdays in June. Using this approach, the anticipated lost workdays are simply added to the durations of the work activities that fall within those respective months (see Figure 5, below).

While this approach is probably the most direct way of ensuring that you’ve accounted for the anticipated workdays lost to adverse weather, it has several weaknesses. The first criticism is that the incorporation of adverse weather days in this manner is not always transparent and obvious. For example, it is not always obvious if and to what extent an activity’s duration was increased to account for time that might be lost to adverse weather. If transparency is important, the obvious solution to this problem would be to identify the number of workdays that represent adverse weather in the activity’s description or name.

The second criticism of this approach is the need to change the durations of the weather-sensitive activity durations when they are delayed from one month to another. For example, as identified above, the number of workdays lost to adverse weather can and does fluctuate from month to month. As such, when weather-sensitive work activities are moved or delayed from one month to another, which is common on construction projects, the durations of the weather-sensitive activities would need to be changed to reflect the number of anticipated adverse weather workdays in the new month within which the activity is now forecast to occur.

Said another way, if an excavation activity is delayed from March into April, there is a good chance that the number of anticipated workdays lost to weather in April is less than in March. If the activity’s duration includes anticipated workdays lost to weather in March, then when the excavation activity is delayed to April, it would be appropriate for the contractor to reduce the activity’s duration to reflect the anticipated number of workdays lost in April. However, this sort of change in an activity’s duration, to reflect the anticipated number of workdays lost to adverse weather when an activity is delayed from one month to another, is almost never done and on large projects would be difficult to maintain on a monthly basis.

Also, it is unusual for a contract to list the number of workdays a contractor should anticipate each month. Most contractors do not increase the duration of work activities based on the month the work is planned to be performed. Rather, they use a thumb rule. For example, one contractor client assumed that it would lose one workday in seven to adverse weather over the life of the project. Using this thumb rule, the contractor increased the duration of activities. Because the thumb rule was based on an average across the entire project, there was no need to adjust durations each month if the project was delayed.

3. Insert an “Adverse Weather” Activity for All Anticipated Adverse Weather for the Project Duration

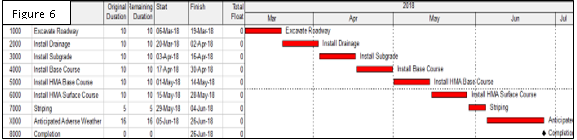

Instead of burying anticipated adverse weather days in the schedule work calendars or weather-sensitive activity durations, another option would be to add an “Anticipated Adverse Weather” activity at the end of the schedule, but before the project’s completion milestone, to represent all of the required anticipated adverse weather (see Figure 6, below).

As the project progresses, and adverse weather is encountered, the duration of this activity is reduced to account for the amount of adverse weather that was actually experienced on the project. This approach is a clean way to account for anticipated adverse weather without having to predict and select the workdays lost to adverse weather in the schedule’s work calendar or bury them in activity durations.

However, a significant criticism of this approach is that on multi-year projects where “all” of the anticipated adverse weather is included at the end of the schedule, the schedule would fail to reasonably forecast the early start and early finish dates for all of the work activities. For example, for the work in the second or third year, the work activities would be forecasted to begin much earlier than would reasonably be expected because the first year of the schedule would not include any anticipated workdays lost to weather. Depending on the project type, this issue may or may not be a problem.

Another criticism of this approach is that the added adverse weather activity would apply not only to the weather-sensitive work, but also to non-weather-sensitive work, as well. This approach may be better suited for projects with shorter durations.

When selecting a method to incorporate adverse weather into their project schedules, contractors should make their decision on a project-by-project basis. Taking into consideration their contractual requirements, the type of project being built, and the project’s location-specific weather conditions when they develop, their baseline schedule will help ensure that they select the best approach for demonstrating that they’ve properly accounted for anticipated adverse weather in their construction plan.

Bill Haydt and Mark Nagata are Director, Shareholders of TRAUNER. Their expertise lies in the areas of construction claims preparation and evaluation, development and review of critical path method (CPM) schedules, delay analysis, training, and dispute resolution. They direct and perform all types of analyses from schedule delay analyses to inefficiency analyses and the calculation of damages.

Bill can be reached at bill.haydt@traunerconsulting.com

Mark can be reached at mark.nagata@traunerconsulting.com

If you liked this article, be sure to sign up on the left side of our website to receive our Ideas & Insights in your email. Be sure to check your email after signing up!